Sinkholes are depressions in the ground that are linked to the collapse of an underground void. Areas that have sinkholes are known as karst terrain or karst topography. How does karst form? There are several steps, starting with the geology:

Rock Type

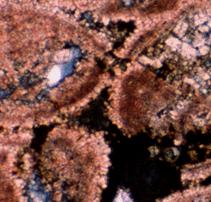

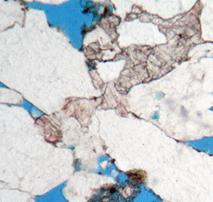

Calcite (below left) is a mineral composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) – similar to the chemical in baking soda. Like baking soda, when vinegar or another acid is added, the calcium carbonate dissolves. Typically the bedrock underneath an area with sinkholes is made of limestone (below middle) which is composed of calcite. Sandstones that contain calcite (below right) also can be susceptible to sinkhole formation.

Calcite crystals (above) – the main component of limestone. Photo from USGS. Click here to read more about the mineral properties.

Peloid limestone of the Smackover Formation – pinkish orange crystals are calcite.

Sandstone of the Donovan Sand– white areas are quartz and feldspar grains and light pink is calcite cementing the grains together.

Dissolution

Rainwater is naturally acidic – not only do raindrops pick up carbon dioxide and sulfur from the atmosphere, they also become more acidic as the water interacts with vegetation. As water moves through the ground and into cracks and crevices of the underlying bedrock, the weakly acidic water dissolves the rock. As dissolving continues, the cracks and crevices become larger, forming caves and caverns.

What does a karst area look like underground? See video Sometimes the subsurface has small voids, and other times it may have larger voids such as caves. Click on the movie to the right to see an example of a cave in an Alabama karst area just north of Birmingham.

Click here to go to the National Speological Society homepage to learn more about caves.

Collapse

When the roof of the cave becomes too thin to support the weight of the ground above, the roof collapses. If the ground above is thin enough, this subsurface collapse can be seen at the surface (below) – this is what we see as a sinkhole.

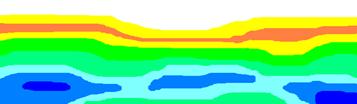

Sinkholes on a map

Example of what sinkholes look like on a topographic map. Sinkholes and other depressions are marked by closed contour lines with hatch marks. Not always perfectly round, some sinkholes may be elongated such as the one in the upper right corner. Other sinkholes may swallow streams or be filled with water such as the one to the right of “Hollow”.