Earthquakes Around the World

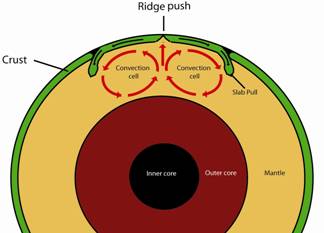

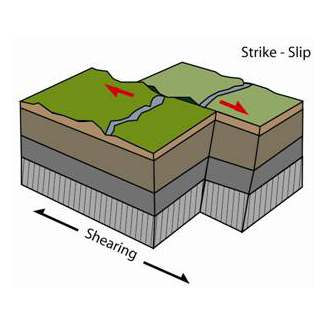

Earthquakes occur around the globe, on every continent and even in the ocean floor. In the maps to the right and below, you can see that earthquakes cluster in particular locations. Most of these areas of high earthquake activity are on plate boundaries. Other earthquakes occur within plates (called intraplate earthquakes). All of Alabama’s earthquakes are intraplate.

Real Time Earthquakes

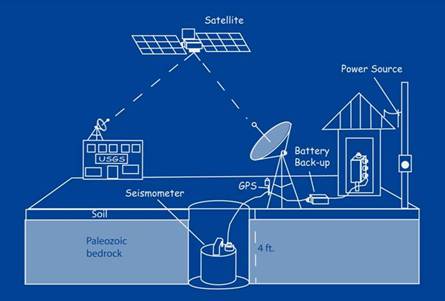

Below is SeismicMonitor – a product of the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) showing real-time global earthquakes of magnitude 4.0 and greater over the last five years. To learn more about a particular quake on the map, click on the epicenter. To see USGS realtime earthquakes in GoogleEarth, click here.